Chapter 4—Slow Flight, Stalls, and Spins

Table of Contents

Introduction

Slow Flight

Flight at Less than Cruise Airspeeds

Flight at Minimum Controllable Airspeed

Stalls

Recognition of Stalls

Fundamentals of Stall Recovery

Use of Ailerons/Rudder in Stall Recovery

Stall Characteristics

Approaches to Stalls (Imminent Stalls)—Power-On or Power-Off

Full Stalls Power-Off

Full Stalls Power-On

Secondary Stall

Accelerated Stalls

Cross-Control Stall

Elevator Trim Stall

Spins

Spin Procedures

Entry Phase

Incipient Phase

Developed Phase

Recovery Phase

Intentional Spins

Weight and Balance Requirements

FUNDAMENTALS OF STALL RECOVERY

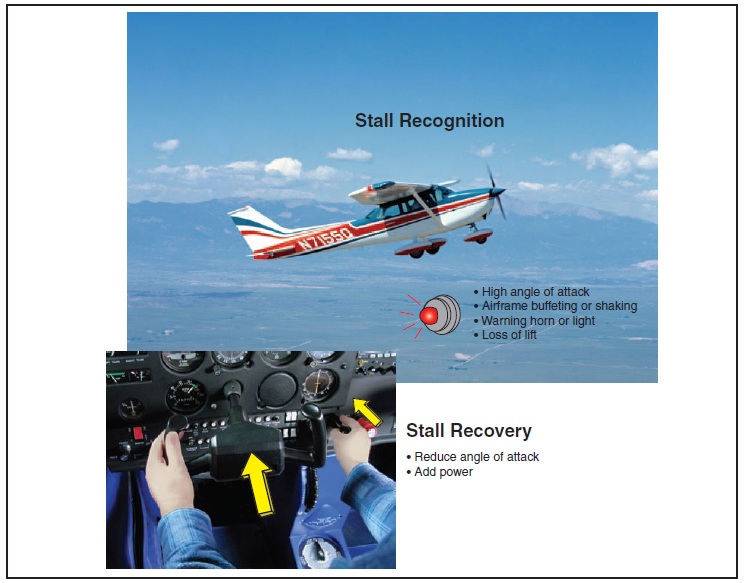

During the practice of intentional stalls, the real objective is not to learn how to stall an airplane, but to learn how to recognize an approaching stall and take prompt corrective action. [Figure 4-3] Though the recovery actions must be taken in a coordinated manner, they are broken down into three actions here for explanation purposes.

First, at the indication of a stall, the pitch attitude and angle of attack must be decreased positively and immediately. Since the basic cause of a stall is always an excessive angle of attack, the cause must first be eliminated by releasing the back-elevator pressure that was necessary to attain that angle of attack or by moving the elevator control forward. This lowers the nose and returns the wing to an effective angle of attack. The amount of elevator control pressure or movement used depends on the design of the airplane, the severity of the stall, and the proximity of the ground. In some airplanes, a moderate movement of the elevator control—perhaps slightly forward of neutral—is enough, while in others a forcible push to the full forward position may be required. An excessive negative load on the wings caused by excessive forward movement of the elevator may impede, rather than hasten, the stall recovery. The object is to reduce the angle of attack but only enough to allow the wing to regain lift.

Second, the maximum allowable power should be applied to increase the airplane’s airspeed and assist in reducing the wing’s angle of attack. The throttle should be promptly, but smoothly, advanced to the maximum allowable power. The flight instructor

Figure 4-3. Stall recognition and recovery.

should emphasize, however, that power is not essential for a safe stall recovery if sufficient altitude is available. Reducing the angle of attack is the only way of recovering from a stall regardless of the amount of power used.

Although stall recoveries should be practiced without, as well as with the use of power, in most actual stalls the application of more power, if available, is an integral part of the stall recovery. Usually, the greater the power applied, the less the loss of altitude.

Maximum allowable power applied at the instant of a stall will usually not cause overspeeding of an engine equipped with a fixed-pitch propeller, due to the heavy air load imposed on the propeller at slow airspeeds. However, it will be necessary to reduce the power as airspeed is gained after the stall recovery so the airspeed will not become excessive. When performing intentional stalls, the tachometer indication should never be allowed to exceed the red line (maximum allowable r.p.m.) marked on the instrument.

Third, straight-and-level flight should be regained with coordinated use of all controls.

Practice in both power-on and power-off stalls is important because it simulates stall conditions that could occur during normal flight maneuvers. For example, the power-on stalls are practiced to show what could happen if the airplane were climbing at an excessively nose-high attitude immediately after takeoff or during a climbing turn. The power-off turning stalls are practiced to show what could happen if the controls are improperly used during a turn from the base leg to the final approach. The power-off straight-ahead stall simulates the attitude and flight characteristics of a particular airplane during the final approach and landing.

Usually, the first few practices should include only approaches to stalls, with recovery initiated as soon as the first buffeting or partial loss of control is noted. In this way, the pilot can become familiar with the indications of an approaching stall without actually stalling the airplane. Once the pilot becomes comfortable with this procedure, the airplane should be slowed in such a manner that it stalls in as near a level pitch attitude as is possible. The student pilot must not be allowed to form the impression that in all circumstances, a high pitch attitude is necessary to exceed the critical angle of attack, or that in all circumstances, a level or near level pitch attitude is indicative of a low angle of attack. Recovery should be practiced first without the addition of power, by merely relieving enough back-elevator pressure that the stall is broken and the airplane assumes a normal glide attitude. The instructor should also introduce the student to a secondary stall at this point. Stall recoveries should then be practiced with the addition of power to determine how effective power will be in executing a safe recovery and minimizing altitude loss.

Stall accidents usually result from an inadvertent stall at a low altitude in which a recovery was not accomplished prior to contact with the surface. As a preventive measure, stalls should be practiced at an altitude which will allow recovery no lower than 1,500 feet AGL. To recover with a minimum loss of altitude requires a reduction in the angle of attack (lowering the airplane’s pitch attitude), application of power, and termination of the descent without entering another (secondary) stall.

PED Publication